Many of us will have heard a sceptic of ADHD argue that it is a strictly modern phenomenon. In fact, those with ADHD-like symptoms have been recognised in some form since the early stages of history, and have most likely existed throughout our history as a species.

Hippocrates

Often referred to as the “Father of Modern Medicine,” in 493 BC Hippocrates noted that some of his patients had, “Quickened responses to sensory experience, but also less tenaciousness [persistence] because the soul moves on quickly to the next impression,” effectively identifying the core symptoms of ADHD: hyperactivity, inattentiveness and impulsivity.

He prescribed these patients, “Barley rather than wheat bread, fish rather than meat, watery drinks, and many natural and diverse physical activities”: a diet low in gluten and high in essential fatty acids, with plenty of exercise. Recent research has found that reductions in gluten can significantly improve ADHD symptoms (link) and a diet high in essential fatty acids may have a similar effect (link), while there is a considerable body of evidence demonstrating the benefits to those with ADHD of regular exercise (link).

Melchior Adam Weikard

In 1775, the German Physician Melchior Adam Weikard was responsible for the first clinical documentation of an ADHD-like condition in modern history. Weikard described a “lack of attention” disorder, identifying many of the significant characteristics that we associate with ADHD today, including distractability (including by one’s own imagination), increased effort required to complete tasks, hyperactivity, restlessness, carelessness and disorganized.

Weikard believed that ADHD was caused by a person’s “fibers” being “too soft or too agile” and therefore lacking “the necessary strength for the constant attention”. His belief was that upbringing was responsible for this phenomenon and the subsequent symptoms, in many ways forshadowing the belief that ADHD is caused by “poor parenting”.

Alexander Crichton

In 1798, Crichton, a Scottish physician, described the inattentive subtype of ADHD in a way very similar to how it is described nowadays. The significance of Crichton’s work was in bringing “diseases of attention” (he devoted a whole chapter to his treatise to “Attention and its Diseases”) among otherwise healthy individuals to the public consciousness, as well as in distinguishing ADHD-type symptoms from brain trauma, which was then thought to be a common cause.

Heinrich Hoffmann

In 1846, a German psychiatrist called Heinrich Hoffmann published a collection of illustrated children’s verses which became popular throughout Europe. Two of the characters featured, “Figety Philip” and “Johnny Head-in-the-Air” might seem familiar to parents of children with ADHD. The first verse from Figety Phil is shown below:

"Let me see if Philip can

Be a little gentleman;

Let me see if he is able

To sit still for once at table."

Thus spoke, in earnest tone,

The father to his son;

And the mother looked very grave

To see Philip so misbehave.

But Philip he did not mind

His father who was so kind.

He wriggled

And giggled,

And then, I declare,

Swung backward and forward

And tilted his chair,

Just like any rocking horse;-

"Philip! I am getting cross!"

Désiré-Magloire Bourneville, Jean Phillippe & Georges Paul-Boncour

Between 1887 and 1910, a group of French physicians published a series of writings focussing on “mental instability” found in schoolchildren. The research the physicians carried out identified the modern-day triad of core ADHD symptoms: hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention.

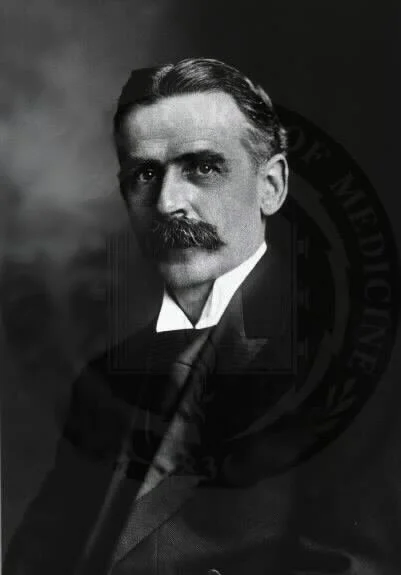

George Frederic Still

In what is often regarded as a breakthrough moment in ADHD entering the public consciousness, Still, a pediatric physician delivered a lecture series in London which was published in The Lancet, one of the world’s most trusted and widely-used medical journals.

Still connected “abnormal psychical conditions in children” to “an abnormal defect of moral control in children”, adding that this “defect” was “without general impairment of intellect and without physical disease”.

Though much of the language and many of the symptoms identified by Still do not appear in the current conception of ADHD, his work represents a key moment in its wider recognition.

Postencephalitic behaviour disorder

For years scientists like Alfred F. Tredgold (1908) had argued for an association between early brain damage and subsequent behaviour problems or learning difficulties. Between 1917 and 1928, an extraordinary phenomenon appeared to confirm this connection, as encephalitis lethargica (coloquially referred to as the “sleeping sickness”) spread across the world, affecting roughly 20 million people.

Significantly, many of the children who survived the epidemic showed remarkably abnormal behaviour, including changes in personality, emotional instability, cognitive defects, learning difficulties, sleep reversals, tics, depression and poor motor control. In the words of one study, they became “hyperactive, distractible, irritable, antisocial, destructive, unruly, and unmanageable in school. They frequently disturbed the whole class and were regarded as quarrelsome and impulsive, often leaving the school building during class time without permission”.

The astonishing and tragic impacts of the epidemic aroused a broad interest in hyperactivity in children and fuelled much of the subsequent research that lead to a formal recognition of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Franz Kramer & Hans Pollnow

In 1932, two German physicians, Kramer and Pollnow, published, “On a hyperkinetic disease of infancy”, whose most characteristic symptom was a marked motor restlessness. They argued that this disease could be distinguished from other diseases with similar symptoms. They described children with the disease as not being able to stay still for a second, running around the room, climbing on high furniture, and who were visibly displeased when prevented from acting out their impulses. This characterization is very similar to our current understanding of hyperkinetic disorder as recognised in the ICD-10 (colloquially referred to as “severe ADHD” or in the DSM-5 as the hyperactive-impulsive subtype of ADHD).

Charles Bradley

Charles Bradley was medical director of the Emma Pendleton Bradley Home (now Bradley Hospital), which treated neurologically impaired children. In 1937, he reported the positive effect of stimulant medication on children with various behaviour disorders (specifically benzedrine (which is no longer in use) for children with excessive hyperactivity).

Despite their research being published in prominent journals, Bradley and his associates made remarkably little impact on research and clinical practice for at least the next 25 years, partly, it has been suggested, because of the contemporaneous popularity of psychoanalytical approaches (and the belief that behaviours have no biological basis and require psychological interventions).

Brain Damage

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, a huge swathe of research appeared to support the theory that behavioural disorders (including excessive hyperactivity) were caused by brain damage. Children with a history of brain injury were found to have developed behaviour disorders dimilar to the postencephalitic behaviour disorder, while studies of birth trauma found a causative link between birth injury and mental retardation in children, and infections, contaminants (such as lead) and epilepsy were all found to be associated with various cognitive and behavioural problems, to name just a few areas of research supporting the theory. One study of children who had suffered from asphyxiant illness in infancy reported the following familiar characteristics:

“a fairly uniform overt behavior pattern in maladjusted children who have experienced asphyxiant illness in infancy. Six cardinal behavior characteristics make up this syndrome and may be listed as follows: 1. Unpredictable variability in mood; 2. Hypermotility; 3. Impulsiveness; 4. Short attention span; 5. Fluctuant ability to recall material previously learned; and 6. Conspicuous difficulty with arithmetic in school.”

With respect to children exhibiting excessive levels of hyperactivity, this was attributed by many to “minimal brain damage”, an idea that had become so widely accepted by the 1950s that evidence of actual damage to the brain was often not sought before its diagnosis was made.

With what we know now of the differences and delays to the development of the brain which underly ADHD, it has been argued that the notion of its intrinsic connectedness to “brain damage” was the antecedent to its recognition as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Methylphenidate

Interest in the treatment of hyperkinetic children with stimulant medication began to grow in the 1950s and culminated in the marketing of “Ritalin” (the market name for methylphenidate) in 1954 to treat hyperactive children. Methylphenidate is now regarded as the most effective psychostimulant and remains the most frequently prescribed.

Minimal Brain Dysfunction

The 1960s saw the emergence of a growing school of criticism towards the hypothesis that minimal brain damage may lead to behaviour disorders. A number of dissentors pointed to the fact that children with hyperkinetic behaviours did not at the same time display any other behaviours that were consistent with minimal brain damage, or indeed have history of trauma or infection in the brain.

It was proposed that a new term be adopted: “minimal brain dysfunction”. As one author put it:

“The term minimal brain dysfunction refers to children of near average, average or above average general intelligence with certain learning or behavioural disabilities ranging from mild to severe, which are associated with deviations of function of the central nervous system. These deviations may manifest themselves by various combinations of impairment in perception, conceptualisation, language, memory and control of attention, impulse or motor function.”

The terminological shift was hugely significant for the development of ADHD as a diagnosis in its modern form, as it differentiated children with minimal brain dysfunction who were within the normal range of intelligence from “the brain-damaged and mentally sub-normal groups”.

Hyperkinetic reaction of childhood

Though it continued to be used well into the 1980s, within research circles it was not long before the term “minimal brain dysfunction” began to attract serious criticism centred around its heterogeneity. It was soon replaced with multiple, specific (and descriptive) labels such as “learning disability”, “dyslexia” and “hyperactivity”.

With respect to ADHD specifically, hyperactivity was by far the most striking of its core symptoms. The idea of a specific “hyperkinetic impulse disorder” was first proposed in 1957; by 1968, it had been formally recognised in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) as “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood”. The manual defined this new disorder as being “characterized by overactivity, restlessness, distractibility, and short attention span, especially in young children” and added that, “the behavior usually diminishes by adolescence”.

Virginia Douglas

By the 1970s, attention began to shift away from hyperactivity towards another core symptom of ADHD: inattentiveness. In 1972, a Canadian psychologist, Virginia Douglas, published a hugely-influential paper arguing that “attention deficit” should be viewed as a more significant feature of the disorder than hyperactivity. Researchers throughout the decade were also finding that this symptom and was responding better to stimulant medication than hyperactivity.

Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) (with or without hyperactivity)

By 1980, the American Psychiatric Association had renamed the disorder as “Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) (with or without hyperactivity)” in the subsequent edition of their diagnostic manual (DSM-III). Whereas deficits in attention and impulse control were now viewed as essential diagnostic criteria for the condition, hyperactivity was not, as the view was taken that the syndrome could occur in two types: with or without hyperactivity. The DSM-III included detail symptom lists for all three of the core symptoms, as well as diagnostic thresholds for severity of these symptoms, to distinguish between those with ADD and the general population.

The significant shift in how the DSM (which was published by the American Psychiatric Association) viewed the disorder marked a parting of ways with the world’s other major diagnostic manual, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) “International Classification of Diseases” (ICD), which continued to focus on hyperactivity as a key symptom of the disorder.

Attention deficit-Hyperactivity disorder

The 1987 revision of the DSM III moved away from the concept of there being two subtypes and combined the symptoms of the three core features into a single list with a single cut-off score.

ADHD as we know it now

The DSM-IV (1994) made several changes to the diagnosis of ADHD, many of which have persisted to this day. Three subtypes were identified: “predominantly inattentive type”, “predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type” and a combined type.

Advances in neuro-imaging throughout the 1990s allowed researchers to confirm that neurological differences existed in those with ADHD, while evidence of workplace difficulties exhibited by those with ADHD in childhood brought to prominence the idea that ADHD may persist into adulthood and throughout the lifespan.

Critics of the DSM-IV and its revised version (DSM-IV-TR (2000)) primarily focussed on their lack of clarity regarding the diagnosis of adults. The DSM-V responded to this with (among other small modifications) a less demanding set of symptom thresholds for diagnosis, including a higher identified age of onset (previously 7, now 12), where the previous thresholds were viewed as ineffective in identifying adults with symptoms. The changes in the DSM-V were much less significant than in previous editions, suggesting that we are beginning to settle on a consensual model for ADHD diagnosis.

Though the ICD and the DSM have now adopted almost identical criteria for the identification of inattentive, hyperactive and impulsive symptoms, the former remains the more demanding of the two.